Postcards from Lapland

In February 2025 I visited my friend and wonderful photographer, Bence Kondor in Kiruna, Sweden. We went on a multiple-day trip into the wild to shoot the beautiful light.

photography

videography

diary

I flew from Berlin to Kiruna with SAS, with a quick layover in Stockholm. As the second leg of the journey began, the landscape transformed dramatically. It struck me that if I had traveled the same distance south instead of north, I would have landed in Tunisia—yet here, I was heading deeper into the Arctic.

Before the trip, I read Lapland by Walter Marsden, which gave me a deeper understanding of the region. I used that knowledge to look for clues in the changing scenery.

Around 10,000 years ago, this part of Europe lay beneath an ice sheet three kilometers thick—taller than the highest peak in Swedish Lapland today. Kebnekaise, at 2,097 meters, would have been completely buried under the ice. As the glaciers retreated, they carved deep valleys, shaped rolling hills, and left behind the countless lakes and rivers that now define the region’s landscape.

landscape near Stockholm

landscape near Kiruna

view of Kiruna before landing, with the LKAB visible in the distance

Kiruna’s airport is small—about the size of a small elementary school. It has a single paved runway, 2,502 meters long, and a staff of around 100 people. With just one gate, the airport handles about five flights a day, most of them return trips to Stockholm. In the harsh winter cold, every plane must be de-iced before takeoff.

Kiruna Airport

Kiruna

Kiruna, Sweden's northernmost town, is a place shaped by extremes—harsh Arctic winters, endless summer light, and the vast iron-rich ground beneath its streets. Founded in the 1890s to support Europe's largest underground iron ore mine, the town grew around its mining industry, drawing workers and settlers to this remote corner of Lapland.

For over a century, Kiruna thrived in its delicate balance between industry and nature. But the very resource that built the town also put its future at risk. Decades of deep mining gradually weakened the ground beneath Kiruna's center, creating the need for one of the most ambitious urban relocation projects in modern history. In 2004, it was decided that large parts of the town—including historic landmarks, homes, and public buildings—would be moved approximately three kilometers east to ensure Kiruna's survival.

Today, this transformation is still underway. Walking through Kiruna, one finds a landscape in flux: empty plots where buildings once stood, entire structures being transported on massive sleds, and fences enclosing soon-to-be-relocated landmarks. Over the next two decades, about 20,000 people will relocate to new homes built around the new town center, with 21 heritage buildings from the old town being preserved and transferred to the new location.

5 , 6 house in the process of relocation

7. Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara AB (LKAB) Fire Station

8. view of the LKAB from a street in Kiruna

Lapland

Torneälven river

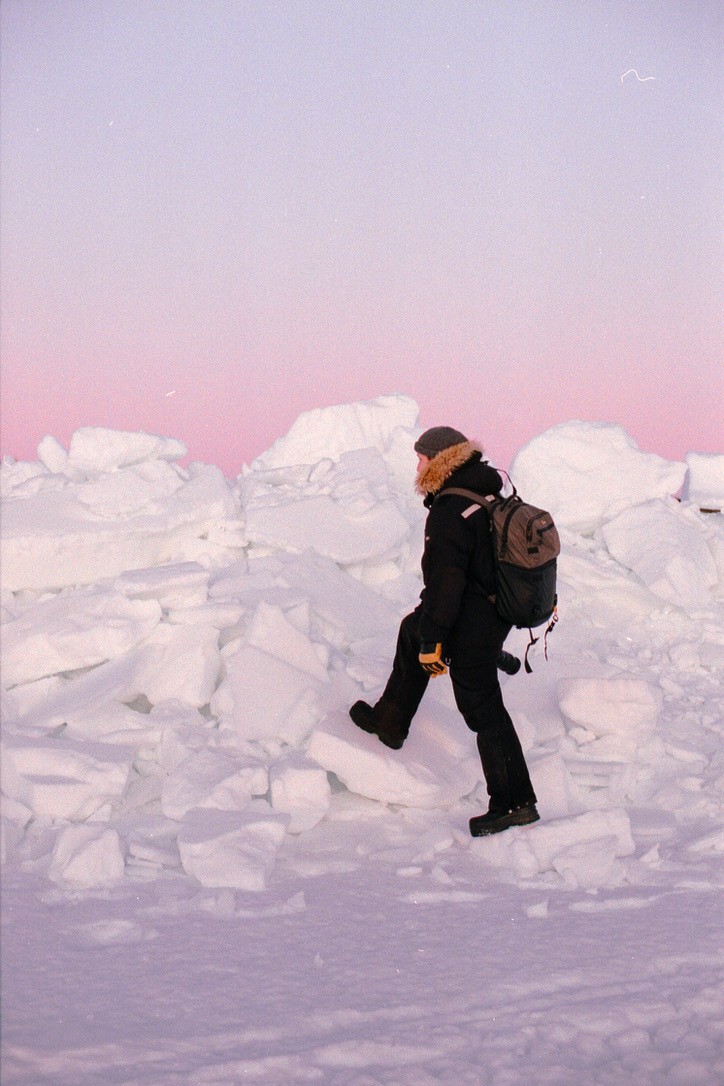

Lapland immediately felt both vast and serene. The Arctic landscape, covered in deep snow, had a quiet beauty unlike anywhere else. In February, the sun lingers low on the horizon, casting long shadows and bathing everything in a soft, golden light—perfect for long photo walks. That was exactly what I had in mind as I set out to explore how people live in one of Europe’s most sparsely populated regions, with just one person per square kilometer.

Life here is calm and spacious, shaped by both nature and a deep sense of trust within the community. I quickly learned that locals leave their cars unlocked, snowmobiles ready to go, and even their front doors open. While it speaks to the region’s low crime rate, there’s also a practical reason—out here, in extreme winter conditions, accessibility can be a matter of survival.

I met a young local woman who asked about my travels. I told her I was visiting a friend and chasing the beautiful light this region is known for. As we talked, I asked what it was like growing up in a place like this. She said it always felt normal that life didn’t slow down in winter, even in total darkness—but what really blew her mind as a kid was that summer nights existed at all. The idea of a sunset in June was as strange to her as the midnight sun was to me. When I told her I’d never seen it myself, we had a good laugh, realizing how much our sense of normal depends on where we’re from.

10 , 11. the Sun around noon

a snowmobile attached to a sled designed for passenger transport

The colorful wooden houses look cozy and inviting, day and night. I love how they complement their environment. I learned that the red color, in particular, has long historical significance. This distinctive shade, known as Falu red, has been used in Sweden for centuries. It originated from the copper mines of Falun in Dalarna, where miners discovered that the iron-rich byproduct of copper extraction had preservative properties. When mixed with water, rye flour, and linseed oil, it became a durable paint that protected wood from the harsh Nordic climate while allowing it to breathe.

Its use spread quickly, not just for practical reasons but also for its symbolism. As a byproduct of mining, the paint was inexpensive and accessible to people from all social classes. At the same time, it mimicked the red-brick facades of European aristocratic homes, giving even the simplest cottages a touch of elegance.

Falu red’s popularity extended beyond Sweden to other Scandinavian countries like Norway and Finland. In Norway, red houses were often associated with fishermen. Over time, the red-and-white aesthetic became deeply rooted in Scandinavian culture.

Snowmobiles driving across the frozen land

With my friend, host, and local guide, Bence, we set out on a two-day snowmobile trip to explore the lakes, rivers, marshlands, and forests surrounding the area. Dressed in thick layers of expedition-grade clothing, with a few rolls of film in our pockets, we aimed to stay as off the grid as possible.

Snowmobiles are fast and loud. The daring ones push them past 100 km/h on the frozen lakes. They’re comfortable and fun to drive but can be rough for those riding on the back seat.

The combination of otherworldly lighting conditions, extreme climate, and the sight of these machines gave me the feeling of being in a Star Wars film. That sensation only grew stronger as night fell, the air dropped to a biting -15°C, and all I could see from beneath the layers protecting me from the elements was the icy, desert-like expanse ahead—just 10 meters illuminated by the headlights.

Before heading out into the wilderness, we made a stop to pick up the essentials for the trip. Since not much grows in this region, most of the food is transported from the south—vegetables, for example, typically arrive wrapped in plastic. One local delicacy, however, is reindeer meat. I was lucky enough to try it, and I found the taste mild and neutral—something that would pair easily with many sides and seasonings.

One of the most important stops, though, was at the candy aisle. There was an entire wall filled with sweets in every imaginable shape, flavor, and texture. It was impressive, and we both filled a paper bag for the journey.

Bence filling a bag with candies

One of the most memorable experiences of the trip happened when we stopped at a tent in the middle of nowhere just before nightfall. We lit a fire inside and cooked beef over the open flames. Realizing we’d forgotten to bring cutlery, we carved makeshift chopsticks from leftover firewood. I still can’t fully explain what makes moments like this feel so special,

but after a full day of exploration, it was a 10/10 experience. Bread, meat, and vegetables had never tasted this good. There’s something profoundly beautiful about sitting on the ground around a fire, eating with sticks, surrounded by silence and snow.

We spent the night in a cabin tucked deep in the woods—completely off-grid, without electricity or running water. I enjoyed the simple effort of making ourselves feel at home: starting a fire in the fireplace for heat and light, slowly warming the room until we could shed our expedition-grade layers and unwind. The crackling fire became both our heating system and our evening entertainment—one of the most relaxing sounds and “TV shows” I can think of.

Another highlight was, naturally, the sauna. In this region, it’s considered as essential as a kitchen—part of the daily rhythm of life. Ours was a small wooden sauna built next to the cabin. Simple, traditional, and with its own fireplace, of course. Within minutes, the temperature climbed to around 70 °C. According to Bence, it’s an incredibly healthy ritual, so we brought a couple of ice-cold beers inside… just to balance out the overwhelming health benefits.

I’d like to end this report with what was probably the most profound moment of the whole journey. Like many others, I had long associated the polar north—above all—with the northern lights. I remember feeling so hopeful on my second flight en route to Kiruna, imagining how we’d be photographing auroras every night. I was so focused on seeing them that, at first, I almost overlooked everything else.

My friend explained that auroras are a rare and special occurrence. The conditions have to align perfectly—you need to be in the right place at the right time. Sometimes they last only moments, sometimes minutes. Sure, locals see them often enough that it becomes part of the everyday—like catching a beautiful sunset in a car park next to the mall.

Since I was staying for almost a week, I had a fair chance of seeing some. I downloaded an app someone recommended to track solar activity and forecast aurora sightings. The first three evenings, I kept refreshing it impatiently, but nothing happened.

Bence has a friend who studies at Kiruna’s Space Science university—his nickname is Space Jan. Just the idea of such a person existing already felt magical. For the first four days, we called Space Jan every evening to get his expert opinion. Each time, no luck.

Eventually, I stopped obsessing and started soaking in everything else around me. Then, on the last night—just as we were getting ready for bed—the phone rang. It was Space Jan. The forecast looked very promising.

I ran outside. A pale green patch of light stretched across the sky—it was happening.

We dressed in seconds, grabbed the essentials, and drove to the nearest dark, open stretch of road. The excitement was surreal. We stood watching, fixated, though at first, nothing much happened beyond faint green glows. Beautiful, yes—but subtle. We began to think that might be it and started packing up.

Then I turned around—just in case.

That’s when I saw it.

A long, wavy stream of green light was dancing behind the pines, gliding closer like a river in the sky. As we watched, the lights deepened in color, taking on reds and forming a kind of translucent veil—like silk in motion. At one point, the aurora wasn’t just on the horizon, it was above us. When I looked up, I saw something I can only compare to an exploding supernova.

I was jumping, laughing, yelling in joy while trying to capture the moment on camera. Some of my favorite images from the entire trip came from those five unforgettable minutes.

That night, I felt my journey had come full circle. I was ready to go home.

Equipment used—for the nerds out there:

Photos: Everything (except the cleaner aurora shots) was shot on my Nikon F2 with 24mm and 50mm lenses

Film: Kodak Gold & Portra 800 — scanned at home and converted with Negative Lab Pro

Videos: Lumix S5 paired with a Canon 16–35mm f/2.8 II (Except for 'Snowmobiles driving across the frozen land' shot on Bence's Canon Eos R6)

Thank you for taking the time to read through this experience.

I hope you enjoyed the images—there were so many more I wanted to include, but this report was already pushing its limits.

A huge thank you goes to my friend Bence for hosting me and making this entire trip possible.

Be sure to check out his incredible work at @kondorbence.